Imagination Becomes Reality

/By Paul Abdella, 2018

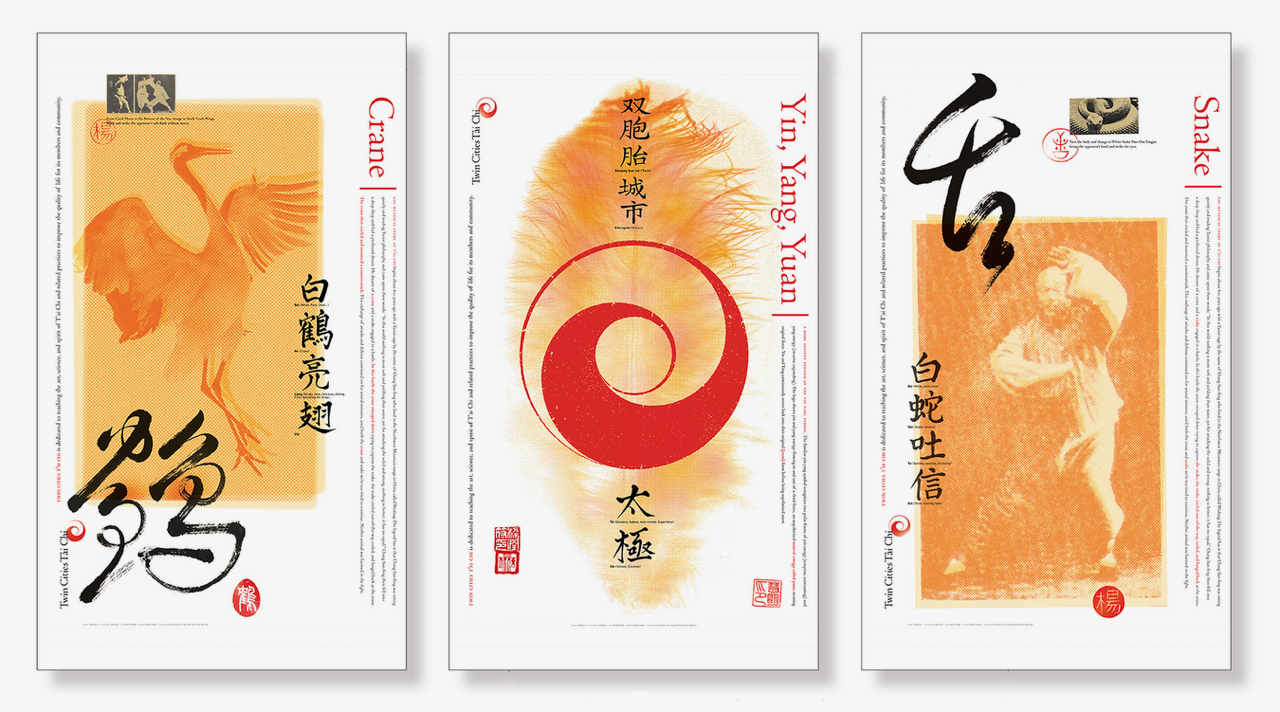

Our studio has been in its current location since 1993. Beginning that year, a demonstration of T’ai Chi was given annually on or around the time of Chinese New Year by members of the studio. In 2002, in the Year of the Horse, studio member Todd Nesser began designing a commemorative poster for the new year and the studio’s celebration. Each new poster featured the animal of the Chinese zodiac for that year as well as images and symbols of T’ai Chi related to that animal. Each poster was unveiled at the celebration and became the centerpiece of the event and hung on the studio’s north wall for the remainder of the year. For 16 years, Todd created a new poster for each coming year. Each poster was unique but united by a common style. It was eagerly awaited each year as a symbol of something new and the year ahead.

In 2017, Todd presented his design for the Year of the Rooster. It was a departure in look and feel that perfectly represented the new direction the studio had taken. In 2018, instead of continuing the familiar animal theme, I asked Todd if he would design a permanent set of posters that would represent the studio and its mission, as well as T’ai Chi and its underlying history and philosophy. He created the three posters that hang at the center of our practice hall. The following is a description of the rich symbolism contained in each poster and shows how the three posters together represent Twin Cities T’ai Chi as a community, as a school that’s part of a larger history, and as a creative source of energy and ideas that is helping to evolve the art of T’ai Chi for future generations.—Paul

The Story in the Posters The mythical origin story of T’ai Chi began about 800 years ago with a Taoist sage by the name of Chang San Feng who lived in the northwest mountain range of China called Wudang. The legend has it that Chang San Feng had a dream of a snake and a crane engaged in a battle. The crane swooped down and tried to capture the snake; the snake circled out of the way, coiled, and lunged back at the crane. The crane took flight and mounted a counterattack. This exchange of attack and defense continued for several minutes until both the snake and the crane were too tired to continue. Neither animal was harmed in the fight.

From this dream, Chang San Feng then conceived of the primary techniques of T’ai Chi based on circularity, the continuous flow of hard and soft, and other Taoist health and longevity practices. As a symbol, the snake represents yin energy: soft, circular, flexible, dark, close to the earth, with the ability to transform itself by shedding its skin. The crane represents yang energy—expanding, soaring, light, close to the heavens—and is a symbol of longevity. A balanced and continuous interplay of these attributes is the essence of T’ai Chi.

The Crane Poster

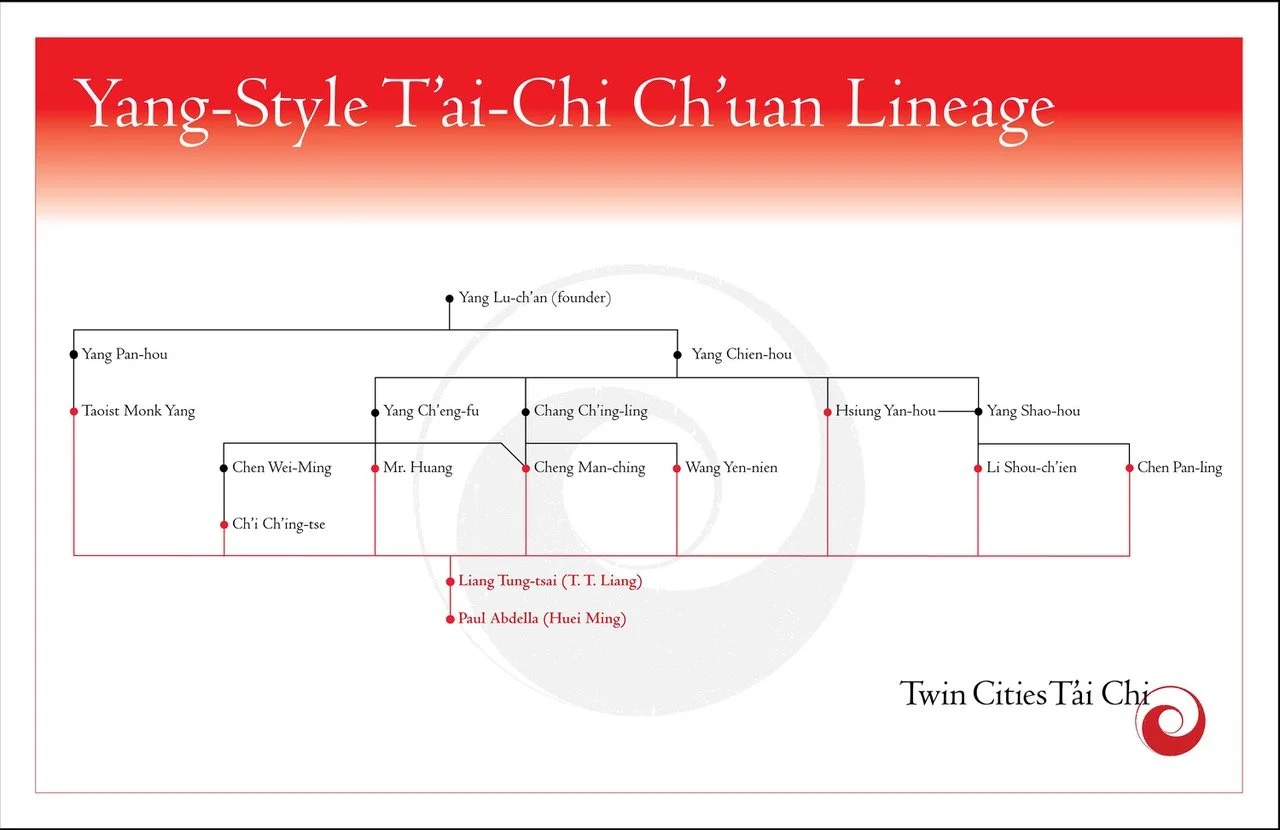

The central image of the crane is seen fully upright and expanding its wings in fa jing— the release of energy. The crane represents yang energy, which is upward and expansive and symbolizes the formless realm of heaven (Tian qi). There are two stamps or seals placed in the upper and lower sections of the poster. Seals are traditionally applied to a piece of artwork to create balance. A yin seal (open with positive line work) balances a yang seal (closed with negative line work). The crane seal down below uses an egg shape, while the Yang family seals are circular and reflect our heritage and style of T’ai Chi. Our T’ai Chi form comes from Yang Cheng Fu, who is pictured performing the posture White Crane Spreads Its Wings, with the Yang family seal stamped over the image.

The movement of Chinese calligraphy is similar to T’ai Chi, especially push-hands. When starting a stroke, you often go toward the opposite direction that the stroke needs to go, resulting in a bone shape. The large calligraphy is in the grass style. Like T’ai Chi, its movement is continuous. Stephen Mao was the calligraphy adviser for the posters, and Todd Nesser was the calligrapher.

The Snake Poster

The central image in this poster shows Yang Cheng Fu demonstrating the posture White Snake Spits Out Tongue, with the snake-like calligraphy overlaying the photo. There is an image of a coiled snake in the upper right that represents yin energy, which is centripetal, contracting, and magnetic. Snakes live close to the earth and symbolize the coiling, receptive energy of T’ai Chi and also its characteristic of adapting to changing circumstances.

A quote from the Yang family on how to apply the posture White Snake Spits Out Tongue sits beneath the image of the snake; the translations are from Jane Schorre.

The Central Poster

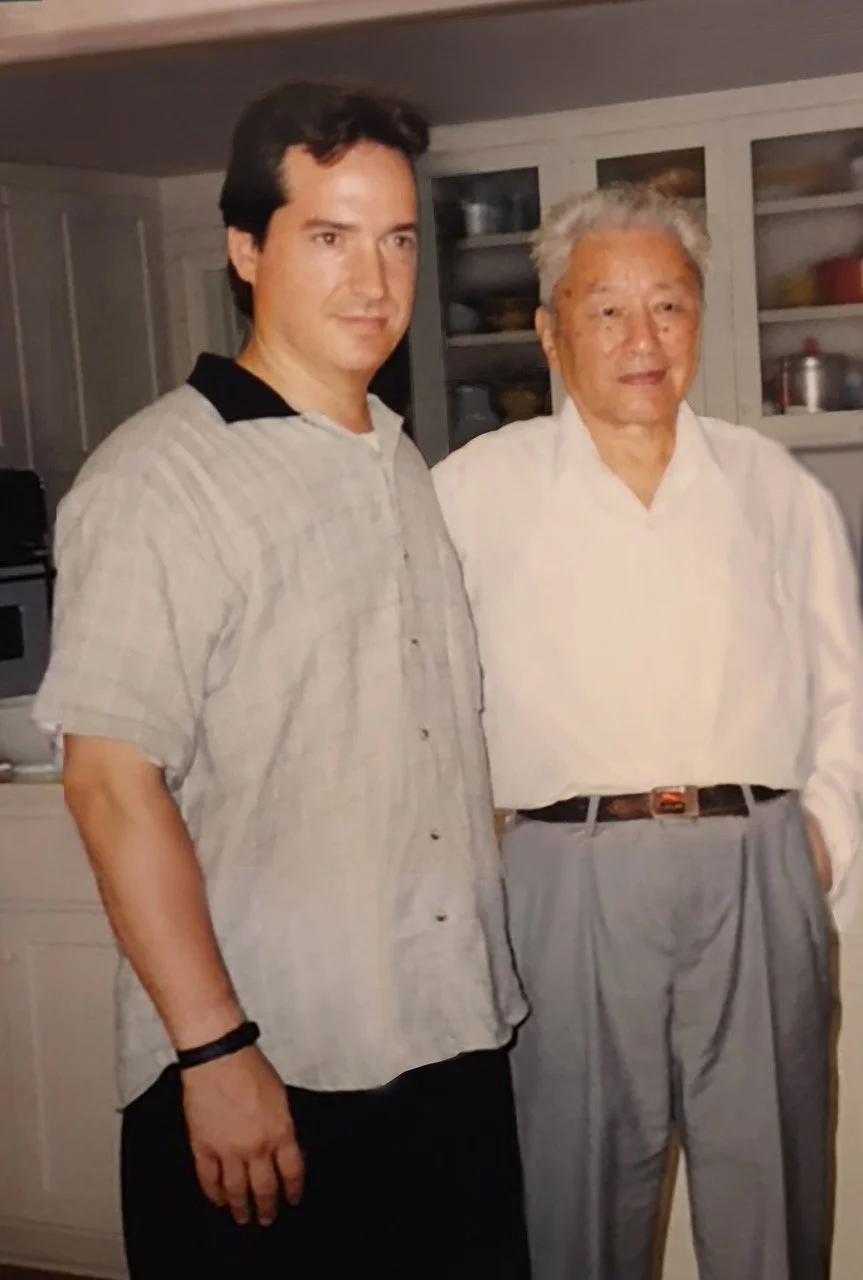

Our studio logo is an ancient symbol that represents three forces in the universe: negative, positive, and neutral—or yin, yang, and yuan to the Chinese. Yin and yang flow out of yuan and continuously revert into their original form before being repolarized. These energies are embodied in the practice of T’ai Chi. The symbol overlays a soft feather that represents two aspects of T’ai Chi practice. The first comes from a line in the T’ai Chi Classics that says, “The weight of a feather cannot be added to the body without setting it in motion,” indicating how the practice of T’ai Chi makes the body sensitive to external forces placed upon it. The second refers to the cultivation of the breath in T’ai Chi to be slow, deep, and subtle so that the soft down of a feather wouldn’t be moved by the breath if it were placed under the nose. Finally, the chop or seal of T.T. Liang sits in the lower left and the seal of Sifu Paul in the lower right, representing the oral transmission of the art of T’ai Chi from generation to generation.

A Meeting of Two Masters

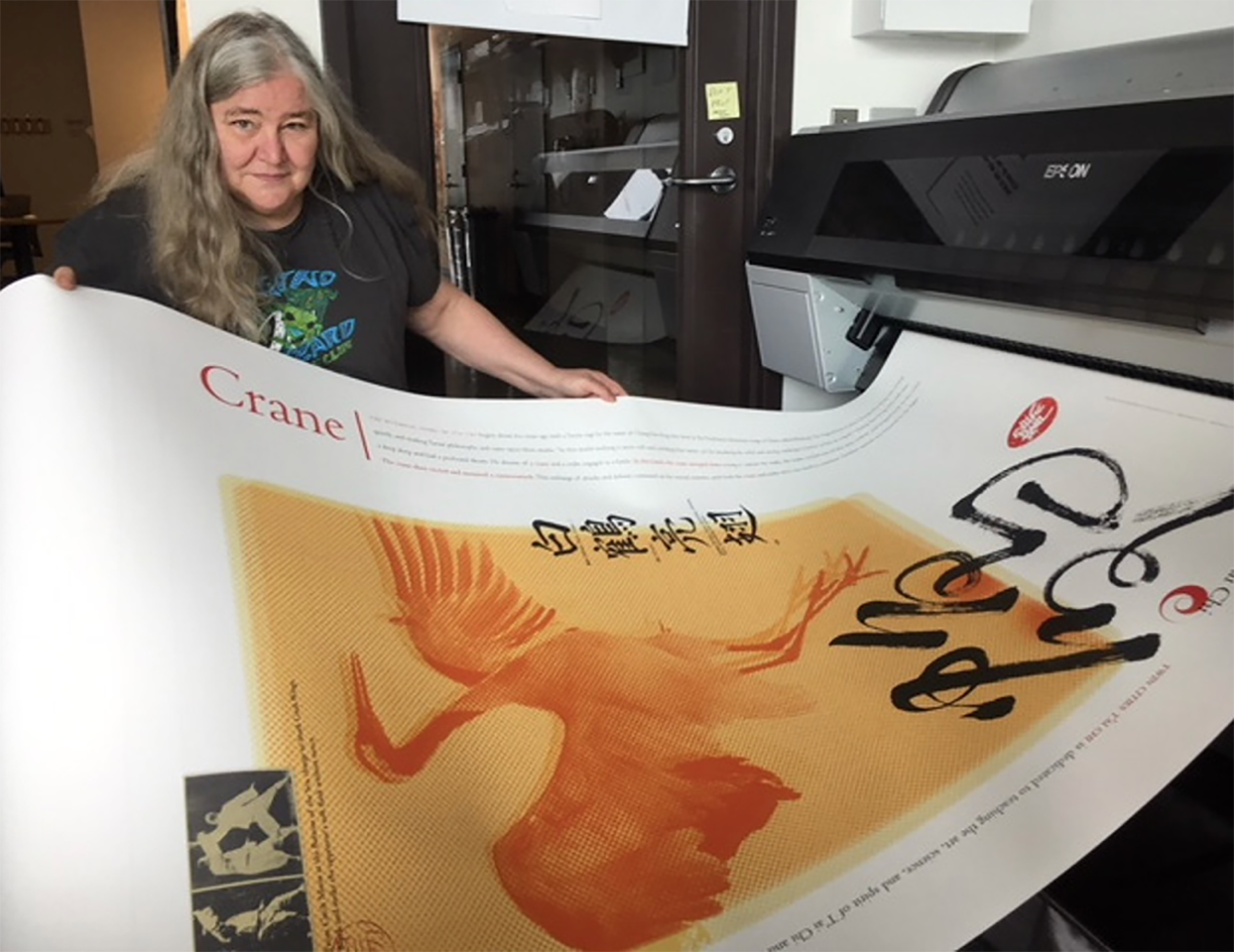

The posters are the result of a collaboration between two masters of their crafts, longtime studio members Todd Nesser and Ruthann Godollei. Todd, a master graphic designer, and Ruthann, a master printmaker and teacher, came together to produce an archival museum–quality print of each poster. Todd’s wife Amy Sparks machine-sewed the top and bottom of each poster to hold the hanging rods for each piece. Art is a language of symbols. The posters are a rich symbol of our studio’s history and mission: Dedicated to teaching the art, science, and spirit of T’ai Chi and related practices to improve the quality of life for its members and community. With deepest gratitude to Todd and Ruthann.